Adrift in a warming world

How disappearing habitats are sending marine mammals into uncharted waters

June 10, 2025

It was the classic European jaunt, the kind that beckons young people with little responsibility and all the time in the world.

The year was 2021. For months, . His adventure began in Ireland, before he hopped his way across the isles of England and landed on the coast of France and then the Spanish city of Bilbao.

He did what any tourist would do: relaxed, watched the crowds, spent his days soaking up the sun, and maybe even enjoyed the culinary delights of northern Spain.

Wally the Walrus was a long way from the frigid waters of the Arctic, where he usually bathed his 800kg physique. But eventually, he found his way home—or closer to home, at least. He was spotted frolicking in the fjords of Iceland at the end of 2021, no worse for wear after his European adventures.

But scientists say his story, and that of many of his compatriots who have wandered well beyond their usual habitats, is a growing trend.

, a marine ecologist in the ľ«¶«´«Ă˝ of ľ«¶«´«Ă˝’s (UOW) School of Science, co-authored a in the journal Marine Policy, which examines the rising number of marine mammals who in recent years have been found beyond their natural habitat.

Dr Katharina Peters, pictured at North Beach in ľ«¶«´«Ă˝. Photo: Michael Gray

The landmark global study, led by Laetitia Nunny, Senior Science Officer at Ocean Care, and featuring the work of researchers from New Zealand, Switzerland, Slovenia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia, has for the first time outlined steps to protect the welfare of displaced marine mammals.

Wally the Walrus, an Atlantic walrus typically found in the freezing seas off Russia, Norway, Greenland, and the eastern Arctic of Canada, would not typically venture into the warmer climes of Europe.

But he is just one of many examples.

The new paper, led by a team of international researchers, outlines many case studies of marine mammals wandering far from home. It is the first time that a study of this magnitude has been undertaken into out-of-habitat marine mammals, a term that applies to creatures that are outside their natural range or within their natural range but in a habitat that is not optimal for their health and survival.

Last year, a beluga, a species noted for its pure white skin, was seen off , far from its usual home in the Arctic. Just a few years earlier, in 2018, a beluga was seen frolicking in the in London before eventually leaving on its own. According to , gray whales have been spotted in the Mediterranean Sea, and a minke whale has been seen near Quebec. Leopard seals, known to live in Antarctica, have shown up on the .

And researchers say more must be done to understand and manage the phenomenon.

A climate-driven exodus?

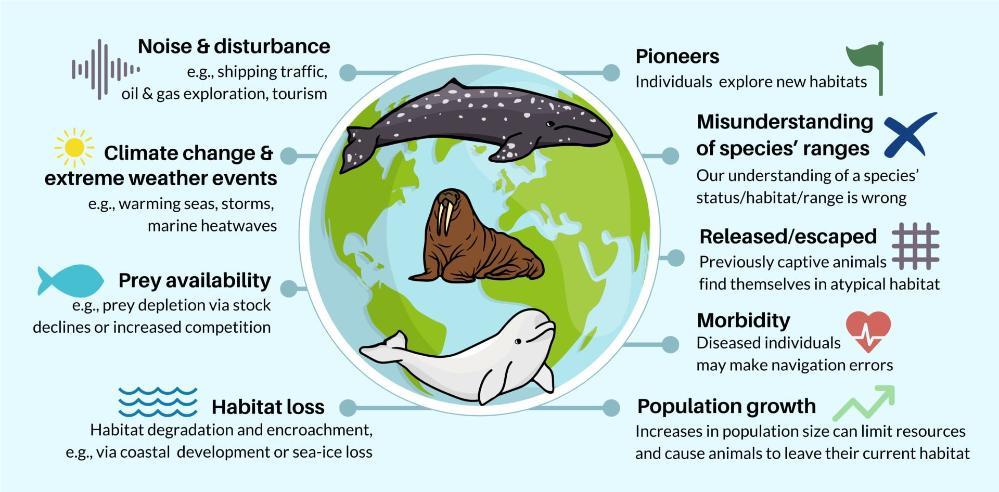

Dr Peters, Research Leader of the at UOW, said the reasons for marine mammals moving outside their usual habitats are complex and can differ from case to case, but the primary drivers are likely climate change and human interference.

“We seem to see more and more marine mammals showing up in places they don’t usually belong,” she says.

“Climate change, habitat loss, and shifting food sources are pushing them into unfamiliar—and sometimes dangerous—territory.

“While these incidents spark curiosity, particularly among the public when they see a marine mammal they are not used to seeing, it is a concerning trend because it increases their risk, and in the past, our way of managing such situations has not always been ideal.”

Minke whale photographed in the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. Photo: MAVE Lab

Sometimes animals find their way into these unique situations, Dr Peters says. Much like humans, they can just wander off track, in the curious search for a new adventure. But the growing rate and the changing climate suggest that these circumstances are often outside their control.

Warming oceans and melting ice are changing where marine mammals live and how they migrate. This can cause cascading effects on the entire ecosystem. If a typical food source has been forced to shift location, the marine mammals that rely upon that food source to survive must also search for new ground—or they must search longer distances or in different seasons.

For example, seals and walruses are among many species that depend on sea ice. As the ice melts or disappears, they lose important places to rest, breed, and hunt.

One of the theories surrounding Wally the Walrus’s journey was that he floated much of the way to Europe on a broken chunk of ice.

“As the oceans get warmer, there are many changes occurring that affect marine mammals in different ways,” Dr Peters said.

“These include melting polar ice, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events such as marine heatwaves. Climate change has the potential to completely upend our ecosystems.

“All these changes are already affecting marine mammals like whales, seals, and walruses. But it can also mean that as weather events become more extreme, marine mammals are impacted too. Storm surges and coastal flooding during hurricanes have, in previous years, carried dolphins into new habitats, which can impact their health and survival.”

The role of humans

Human activities are changing and damaging the places where marine mammals live. This is occurring in myriad ways—by building physical barriers in the water, developing pristine coastlines, changing prey abundance via overfishing, polluting the ocean with chemicals and loud noises, or simply disturbing animals with our presence.

Loud noises in the ocean, such as those from ships, construction, or military sonar, can be especially harmful to whales, dolphins, and porpoises. These sounds can scare the animals away from their usual homes. In some cases, they may leave an area for a short time, but sometimes, they never come back. For example, gray whales stayed away from one of their favourite breeding spots for more than five years because of loud industrial noise. Similarly, porpoises have been seen avoiding areas affected by underwater construction.

Humpback whales photographed in Eden, South Australia. Photo: MAVE Lab

It is a real concern, Dr Peters says, that humans can make life harder for marine mammals.

“It is not just big industries that cause problems,” she says. “Even everyday activities such as boating and swimming, or people walking near resting seals, can disturb marine mammals and make them move away from important resting or breeding spots. Human actions, big and small, can force marine animals to leave their homes in search of safer and quieter places.”

But this tension between humans and marine life reaches its peak when it comes to managing the risks to animals who have strayed too far from home.

“Often marine mammals stay along coastlines, which means they are easy to spot by the public. It can be a true source of joy for people to see a species that they would not usually see. But this also leaves the animals incredibly vulnerable. Concerned members of the public might take it upon themselves to try to ‘help’ the animal or interact with them directly.

“For the most part, these situations involve wild animals, so it places a great risk to the human of disease, injury, or death. It also places a great risk to the animal, particularly if it is in distress. Marine mammals often develop a high public profile through media attention, and they can be seen as both a flagship for conservation and a lightning rod for controversy.

“Out-of-habitat marine mammals have also been killed by authorities who have deemed them a threat to public safety, even when there was no evidence of that.”

Dr Peters says marine mammals will likely continue to venture outside their habitats more frequently—and the public and powers-that-be must understand how to handle these situations without causing harm.

Education, communication, and people management are the pillars of managing the conflict between marine mammals and humans. It is essential to educate the public about the risks of interacting with wild animals, while agencies and governing organisations need better training and enhanced protocols to guide their decision-making, with a focus on how to manage and mitigate the impact without harm to the animal in question.

Dr Katharina Peters. Photo: Michael Gray

Marine mammals who have emerged in unusual places should be continuously monitored to ensure that any interventions - to remove them or even help them - are in the best interests of the animal’s welfare. The idea, Dr Peters says, is to begin with the least invasive methods possible, such as deterrents or physical barriers, before resorting to capture and relocation.

“It is important that management authorities, organisations, and individuals work collaboratively to protect animals in these often unique circumstances,” she says.

“Animals don’t understand that they are causing havoc or that they have ventured outside their usual habitats. It is not their fault. Indeed, some of these creatures are pioneers, the first in their species to search for a new place to live as climate change disrupts their way of life.”